The Community Concourse, Reimagined

Carrying forth a long tradition, today’s cultural hubs stand to testify: If you build it, they will come.

On September 24, 2016, President Obama introduced the last full site on the National Mall — the National Museum of African American History and Culture. To a crowd of 7,000 invited guests (and thousands more watching on Jumbotron nearby) he celebrated the completion of this testament to the country’s narrative, a museum that takes visitors on an emotional eight-floor journey through slavery, emancipation, segregation, and forward into a brighter future. “I, too, am America,” he said, paraphrasing Langston Hughes.

“It is a glorious story, the one that’s told here… And it’s a story that perhaps needs to be told now more than ever.” As visitors toured the 400,000-foot structure, many were both elated and overcome.

Overnight, it became the most exciting site in our nation’s capital. Opening weekend tickets sold out within an hour. Two days later, advance entry tickets were booked solid through the end of the year. In a city of museums, NMAAHC still manages to be a blockbuster, proving that dynamic cultural institutions have the power to draw visitors — locals and out-of-towners alike — like nothing else.

Inventively conceived by architect David Adjaye, the physical structure has helped to — subtly, elegantly — redefine the landscape of the National Mall. “It’s an enormous museum, but most of it is underground,” says Kriston Capps, a writer for The Atlantic’s CityLabs. “What you see is a jewelbox that fits existing sight lines and suits its neighbor, the Washington Monument, but what you get is a much, much larger museum that’s invisible.” Four underground stories keep the profile understated, but the massive steel and glass box above is enveloped in a series of rising coronas (a reference to the capitals of Yoruban columns) and sheathed in a bronze-coated aluminum grill inspired by those found in African-American communities in Charleston and New Orleans. Outside, a substantial covered porch, plentiful seating, and rippling water invite guests to convene in the shadow of the structure, taking in quintessential Capitol Hill views.

If Adjaye’s creation exhibits the vitality of cultural landmarks, it’s only the latest in a string of recent successes around the country. In Miami, the once down-at-heel warehouse district of Wynwood has transformed into some of the country’s most in-demand real estate, largely thanks to a partnership between developer Tony Goldman and a community of brilliant graffiti artists, who made endless, windowless factory walls into their canvas.

In New York City, countless similar projects have revived neighborhoods, but none in recent memory was so effective as the renaissance brought on by the Brooklyn Academy of Music in Fort Greene. Extant since 1861, BAM established itself as a champion of progressive performance by the 1960s, eventually tasking world-class architect Hugh Hardy with transforming the decrepit Majestic Theater into the eponymous Harvey Theater (no stretch for the performing arts specialist, who also worked on Radio City Music Hall and Lincoln Center).

It’s now the most in-demand space within the BAM campus, which is currently undergoing a $25 million initiative that will physically link their three facilities. The surrounding area, known as the BAM Cultural District, is among Brooklyn’s most desirable neighborhoods, with construction of a 32-floor, residential high-rise, BAM South, currently underway.

And American cities should prepare for more culture shock. In 2018, The Nader Latin American Art Museum will open in the heart of Downtown Miami. When it does, it will be the largest museum of Latin American art in the world. Designed by Mexican architect Fernando Romeo, the plan features four colossal terraces rotating on an axis for pedestrian use, a performing arts center, and restaurant, plus two residential towers that will help fund the museum.

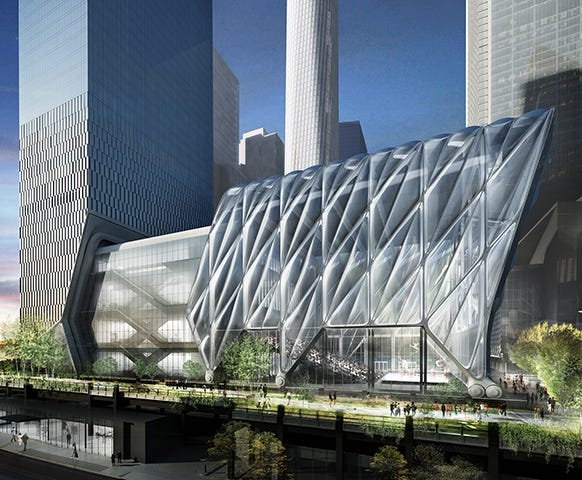

In New York City, Diller Scofidio + Renfro and the Rockwell Group have designed the much-anticipated Shed, a six-story visual and performing arts center with an expandable 16,000-square-foot ‘roof’ that extends from the façade to house additional events (New York Fashion Week has been eyeing the site eagerly).

On the West Coast, San Francisco may be the most exciting site for arts expansion — not with a museum or theater, but an entire island. A former World’s Fair site, and later a naval base, Treasure Island was recently approved for a $1.5 billion redevelopment project. This promises 8,000 new housing units on the man-made island (no small prize in one of the country’s most expensive housing markets), as well as 500 hotel rooms, a new ferry station, and an agricultural park, but most interesting may be the $50 million allocated to public art on the island. This could take the form of sculpture, light displays, performances, and festivals, and promises a draw to the space that exceeds the promise of a cheaper apartment or skyline views.

The potential is limitless, and today more than ever, it’s spaces like these that beckon us beyond our doorsteps. As new landmarks dedicated to our past and present rise across America, we owe it to ourselves to come together and see them firsthand.

Places like the NAAMH and BAM, and one day, Treasure Island, are what define our cities. And what are cities if not the very intersection of humanity?

Reconstructivism

Not every arts center needs to be brand new. Here, a look at three renovated spaces that just needed to have a little work done.

Kings Theater, Brooklyn

For more than three decades, New York’s fourth largest theater sat decaying in Flatbush. Built in 1929 as a Loew’s movie palace, it found its second act in 2010, when Martinez + Johnson Architecture mounted a massive renovation. Diana Ross headlined at the Kings’ 2015 reopening, and acts like Patti LaBelle and Bon Iver pass through regularly.

SFMoMA, San Francisco

Less a renovation than an entirely new building that intersects with the old, Snohetta’s 10-story addition to the 20-year old existing structure makes it the largest contemporary art museum in America. Exhibition space has leapt from 69,000 to 460,000 square feet of work by Pablo Picasso, Diane Arbus, and Jasper Johns.

Boston Central Public Library, Boston

“We never did get the entrance straight,” Philip Johnson once said of his 1972 addition to Boston’s Central Library. In July, William Rawn Associates finally rectified the problem: taking tint off the windows, removing a series of embankments that barricaded the building from the street, knocking down interior walls and opening the lobby into a welcome area.